One of the things I’m still getting used to about Canada is that relative to the UK, everything is so new. In the UK, buildings that are a couple of hundred years old are sometimes barely noticed due to their ubiquity, whereas here, they are awe-inspiring singulars. So, in British terms, Regina is quite young - it just celebrated its 140th birthday - but it still has some fascinating history.

Whatever its age, the earliest days of any institution are among the most interesting as it tries to define itself by identifying and developing its philosophies, and to promote itself through the foundational myths it creates. Why else would the western be the archetypal American film genre?

But of course “history” often prefaced by a silent “white”. Columbus didn’t “discover” America (even if he had actually managed to land there rather than on Cuba). There was a large and diverse population with a long history and a rich set of cultures and traditions already living there. Even ignoring the twenty or so years Leif Erikson hung around Newfoundland around 1000AD, the Italian John Cabot didn’t “discover” Canada for his English paymaster Henry II in 1497, and Jacques Cartier didn’t “discover” another bit of Canada on behalf of France thirty-eight years later.

But, for the next few paragraphs it’s more recent history that I’ll be looking at, and specifically the railways.

In the 1880s Saskatchewan didn’t exist - it was still the North West Territories (not to be confused with today’s North West Territories) and Regina was named its capital in 1883 (the whys and wherefores will make an interesting post for another day). Initially, it grew quite slowly, but the arrival of the railways led to a massive expansion, particularly in the early years of the 20th century.

To help that process, the federal government donated 4,000 vacant lots just north of the existing Canadian Pacific Railway line, reserving them for commercial and industrial use and railway services. This became the Warehouse District, between Albert St and Winnipeg St (west to east) and 4th Ave and Dewdney Ave (north to south).

Thus Regina became an “instant town”. While local businessmen built their homes further south, on the other side of the tracks, around what is now Victoria Park (then Victoria Square and without the subsequently planted trees), they promoted the city and their (mostly retail) businesses on what was then South Railway Street - now Saskatchewan Drive, by erecting Potёmkin stores - wooden frontages with nothing behind.1

The railway also had a military use. The Métis, Cree and Assiniboine were among the indigenous tribes who felt their rights and land were threatened by the Canadian government and in mid-1885 Louis Riel led them in the North-West Resistance, a five-month armed uprising. The government used trains to transport troops from Eastern Canada as far as Qu’Appelle, from where they marched northwest to the battlefield.2 Riel was a divisive figure even among potential supporters and when the Resistance failed, he was tried and hanged, and for many years villified by Anglophone Canada. The railway system continued to grow including, five years later, the opening of the Qu’Appelle, Long Lake and Saskatchewan Railway linking Regina to Saskatoon and Prince Albert. Neither branch now takes passengers.

As in the UK, the development of railways in Canada depended on free-market entrepreneurialism and is thus a history of corporate rivalries leading to a complex of plans that duplicated routes, gave small places disproportionate importance while other larger ones were missed altogether and positioned stations strangely in deference to local objections, or which came to nothing all, or were completed but failed, leading to bankruptcies or mergers, that led to entirely new complexes of plans that duplicated routes … 3

The fine detail is beyond this post but the burst of activity in Regina included the arrival of the Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) in 1908 and the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in 1911, which merged to form the Canadian National Railway (CNR) in 1918/9. In the meantime, around 1911/12, they had started to build distribution warehouses so that Regina finally became a major hub. Transportation of large quantities of freight was still reliant on the railways and the network expanded to facilitate that, with lines to what would now be considered minor outposts, with a corresponding growth in employment and economic activity.

The expansion continued with the development of mail-order centres for the Robert Simpson Co (1858-1991) and the Eaton Co (1869-1999) and, in 1928, General Motors’ first assembly plant in Western Canada. Through the first half of the 20th century the warehouse district was the commercial and industrial centre of Regina - which is where we came in.

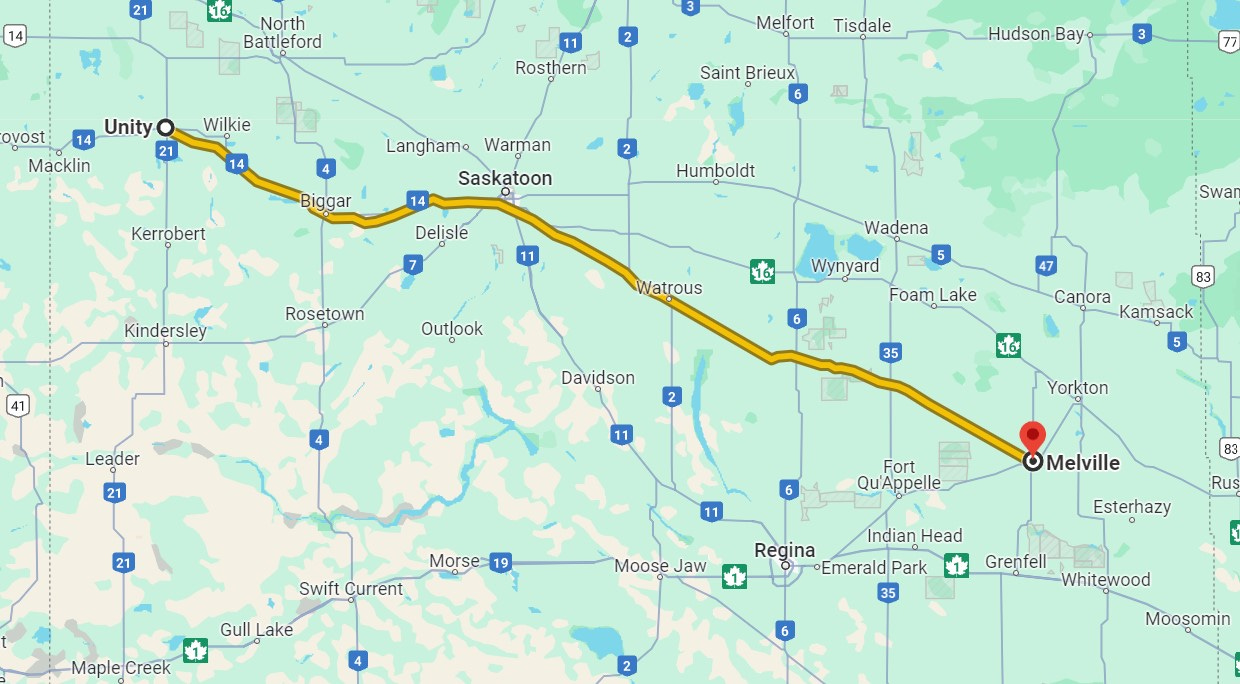

The current Saskatchewan rail network looks like this:

There’s a bigger version here.

Though eventally many of the warehouse operations closed, the buildings remained and increasingly have been repurposed for businesses or housing, as listed here. It’s a slightly odd area, with views over the railway sidings, some empty lots and a disparate range of businesses, some funky and some workaday. We popped into a set of antique salerooms. It was a rum old mix: bits of dusty kitsch with a hopeful ten-buck price tag and some really nice furniture that might even have been worth the four figures being asked. Among several brewpubs and bars, there’s the Bushwakker Brewpub, a bit of a local institution that serves very good beer and very large helpings of food. If it’s the architecture that attracts you, there some interesting industrial buildings that you can see on the various self-led walking tours.

1170 6th Avenue was designed by Storey and Van Egmond and built (for $50,000) in 1912-15 for the wholesale grocers H.G.Smith Ltd, with some alterations in 1919. Storey and Van (as he was known) did a lot of work in Regina and they’re discussed quite a bit at Regina Urban Ecology. As well as Smith, it was tenanted at various times by Robert Simpson Western Ltd (1939-1954), and the Army & Navy Department Store. It was refurbished in 2005 to accommodate businesses on the main floor with loft condominiums above.

Just opposite is 1175, also built in 1912 for the Saskatchewan Motor Co. and later used in turn by Quaker Oats, Ames-Holden Tire Co. and, from 1922-53, the Steele Briggs Seed Co. It was one of the first repurposings when, in 1987, it became an antiques mall.

But as cars became more ubiquitous, passenger rail traffic fell across Canada and in 1989 Brian Mulroney’s Conservative government announced a huge package of cuts aiming to control the spiralling subsidies.

Hence the weird situation where since 16 January 1990 Regina, the provincial capital and (by a smidge) the second largest city in Saskatchewan after Saskatoon, has had no passenger railway. The railway we’ve intermittently seen through the trip - and which does run through Regina - is a freight-only line and for long stretches is single track. In fact, the lines on the map above are mostly freight and the different colours designate the different operators.

There are, in fact just five passenger stations in Saskatchewan, with about 530km between the outermost ones, a journey taking around eleven hours:

Melville (pop c.5000) - Saskatchewan’s smallest city

Watrous (pop. 1,800).4

Saskatoon (pop. c.266,000) - Saskatchewan’s largest city

Biggar (pop. c.2,100).5

Unity (pop. c 2,500)

This means that of Saskatchewan’s population of 1,221,000, around 276,000 people have direct access to a railway. But then again, unlike London (England), there’s no real call for commuter services: people work either in the city or near where they live, so perhaps it’s academic. And once you’ve got your car for your relatively short commute you might as well use it for longer journeys. That 11-hour train journey from Melville to Unity is a leisurely six-hour dive.

It’s another way in which I’m having to get used to being An Englishman Abroad.

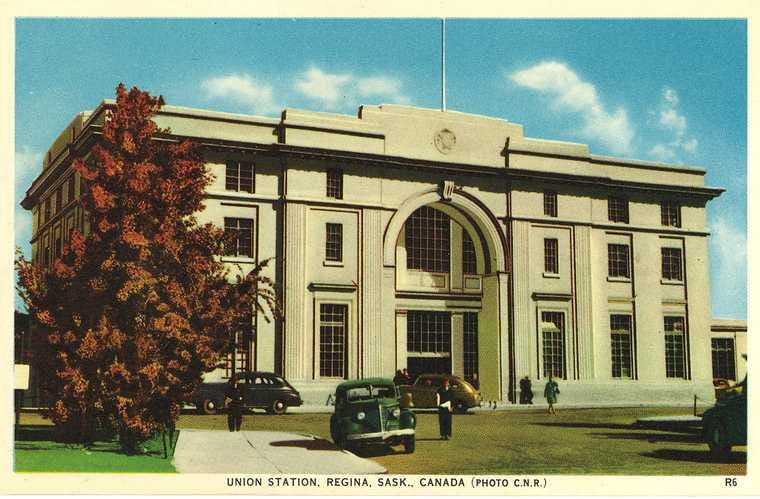

Still, Regina does still have a very nice railway station.

However, after five years of being vacant, it was turned into a casino. It has a large car park

The story of Grigorii Potёmkin erecting a series of impressive facades to fool Catherine the Great is a myth. She wouldn’t have been fooled for a moment. But this is just one of several … errrrr …. myths about the Scarlet Empress. While I may have erred in your eyes by including this falsehood, I stand by my decision to include the diacritic to indicate that the proper pronunciation is (with the stress indicated by capital letters) “PotYOmkin”.

You’ll also see it called the North-West Rebellion, the 1885 Resistance, the Northwest Uprising, the Saskatchewan Rebellion, and the Second Riel Rebellion. Together with the Red River Rebellion, they are referred to as the Riel Rebellions.

Pierre Berton wrote a two-volume history of the building of Canadian railways. The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 (McLelland and Stewart, 1970) and The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (McLelland and Stewart, 1971). They were abridged into a single volume in 1974 and became the basis of an eight-hour TV Miniseries, The National Dream (CBC, 1974). Both single volumes are now available from Penguin.

UK readers should note that this is not pronounced “Waitrose.” That is not the only difference between the two.

Despite what the Saskatchewan government website might imply, what they call Bigger [sic] is not twinned with another town called Smallar, but is named after lawyer and politician William Hodgins Biggar (1852-1922) who was vice-president of the Grand Trunk Railway. https://www.saskatchewan.ca/residents/transportation/rail/provincially-regulated-shortline-rail