We all end up in the cemetery. And for visitors to Paris, that means Père-Lachaise.

It was baking hot the day we went. The cobblestones had spent days greedily gobbling up the heat and were now spewing it back as hard as they could, in competition with the sun itself.

There’s no order to who is where, no sections dedicated to writers, politicians, etc., so if you are star-spotting you’ll need to consult the map to plan a route like one of those “Touch every dot using the minimum number of straight lines” puzzles. But we didn’t have a plan as such, no trainspotter’s list of graves to tick off. Writers? Composers? Artists? Politicians? There are enough here to satisfy many a taphophile. Rather we’d walk around to see what we would see. More democratic that way. The famous don’t always have the most imposing graves and it’s worth seeing the rich people’s to remind ourselves that this is where we all end up and the stones we pile on our coffins make no odds. Regrets? I’ve had a few.

I’m the end of my line so I won’t be long in the ground before people forget and whatever’s there becomes another colossal wreck. Probably better to follow my parents, who went into the fire and were scattered at the crematorium on damp windless days so that, I suppose, not too much of them was blown beyond the rose garden.

We started up the hill. Nobody famous but a series of family memorials, looking like ornate telephone boxes from the late 19th and early 20th centures. I suppose there were off-the-shelf models with a series of optional extras; a pragmatic mix of table d’hôte and à la carte. Inside, shelves for your relatives’ memorial candles, and maybe stained glass windows or tiles with suitably consoling images of angels to accompany you to Heaven and introduce you to Christ, who also appears regularly.

A moment of glory in an austere interior. The door to your minicrypt might be iron, pierced or wrought with glass inserts.

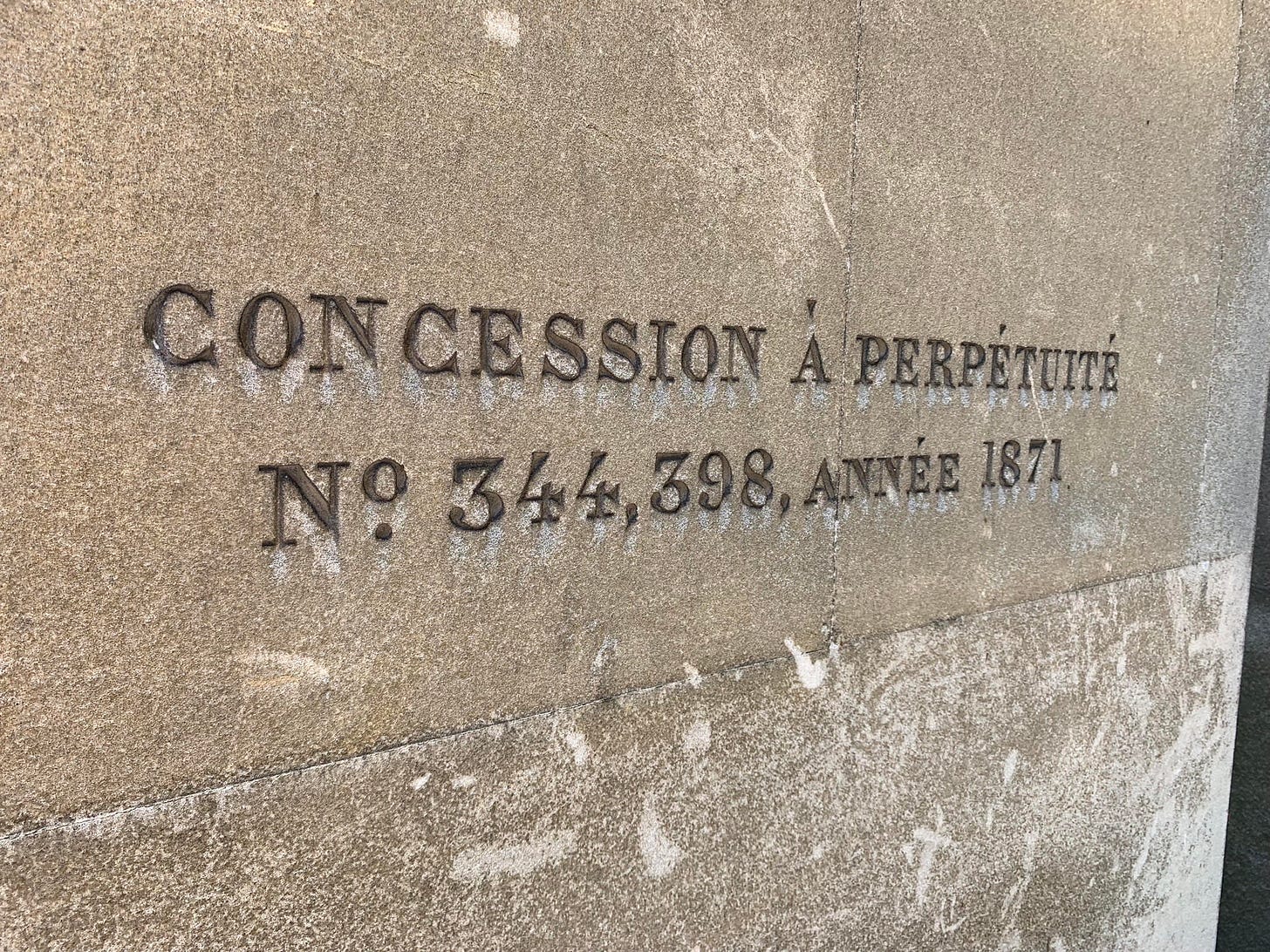

Somewhere will be a list of the memorialised, for these are not usually solely occupied. Some lists are long and intergenerational, and some embrace multiple, presumably intermarried family names. Who’d want to be buried with strangers? At least not in the same hole. You have no choice in who is next door, sometimes so close that no light troubles your stained glass. But at least you know you won’t be disturbed in the future: each one carries a Concession à Perpétuité.

But for all that promise of permanence, most are less than pristine. The interior shelves droop, votives collapsed and dusty, doors hang off, stained glass panels are missing. Maybe even fallen down entirely.

Time’s wingèd chariot. And yet amongst all this, one, most fragile, looking oddly like a greenhouse, has survived intact.

Others are judged important monuments. The most impressive/ludicrous sits at the centre. We initially mistook the 20-metre column for the crematorium chimney. Beneath it lies Félix de Beaujour (aka Louis Félix-Auguste-Boujour, 1765-1836), a diplomat, politician, historian and French Ambassador to the United States who has, even in French, a surprisingly short entry on Wikipedia. Sic gloria…

A weird Orthodox Russian style cabinet stands tribute to Princesses Zinaida Dolgoruky (1817-83) and Vera Dolgoruky (????–1919). Both were part of a vast Russian dynasty within the vast Russian aristocracy and married into the Lobanov Rostovs, part of a vast Russian dynasty within the vast Russian aristocracy. Dolgoruky means long-armed and Lobanov means wide-foreheaded but neither feature is visible in the sculpture on display here. For reasons unknown, they live in eternity with Amédée Dailly, the Mayor of Viroflay (near Versailles) from 1855 to 1871. You might think the glass that now protects the sculptures is a response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, protecting it from counteroffensive iconoclastic attacks but for whatever reason, it’s been there for twenty years.

Elsewhere we bumped into some more obviously famous people, with varying memorialisations and some odd neighbours. Molière (1622-73) and La Fontaine (1621-95) sit side by side in a fenced plot. Probably they would have understood each other, with their wit and sardonic outlook on life. Molière may have appreciated the irony that, though actors could not be buried in sacred ground when he died, in 1817 he (or whatever remained of him after 144 years) was moved to Père Lachaise to honour his achievement. La Fontaine beat him to it, being moved to his new resting place when the cemetery opened in 1804.

But what would arch-realist novel-factory Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850) have made of Gerard de Nerval, who lies opposite? The 19th-century proto-surrealist poet is probably most famous now for taking Thibault, his pet lobster, for a walk on a blue ribbon in the Palais-Royale. Now, his best known line may be “Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie” from his poem El Desdichado, and that only because it turns up as one of the fragments shored against Eliot’s ruin in The Waste Land. It’s oddly appropriate; the column, albeit topped by a vase, seems oddly abbreviated - a traditional symbol of promise cut short, as was Nerval’s by his suicide in 1844 after years of mental illness. Thankfully, even after 179 years, someone does care and has printed out his poem Vers Dores, with the line “Tout est sensible!” Like his lobster.

It would be impossible to cover all the famous graves in a day and some, beyond paying respects, may not justify the trip. As much as I love Georges Perec (1936-82), his grave is a plain recitation of facts, rather than the sly set of puzzles, jokes and Oulipisms that it could have been. Though an incredibly successful and influential playwright, Eugene Scribe (1791-1861) may be best known now as a librettist for grand operas by Meyerbeer, Verdi and others. He's got a large, if slightly standard issue obelisk.

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) has two bronzes: himself, brush and pallete in hand, lying across the plinth on whose side is a bas-relief of his most famous painting Le Radeau de la Méduse.

You might have expected Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) to be similarly honoured with a reproduction of La Liberté Guidant le Peuples, but he just has a massive block of granite. Perhaps it was thought his fame made illustration redundant.

But a lot of people go to Père Lachaise for one of two graves: Jim Morrison or Oscar Wilde, both objects of veneration (at least in death). They’re about as far from each other as they can be (what posthumous conversations they could have had!) and hot, thirsty, tired and hungry we decided to skip the leather-trousered beatnik.

Perhaps the heat had dissuaded other people as well; we arrived to find just two. A Chinese couple repeatedly took turns to photograph each other reading Wilde. A couple of women sauntered up but after a quick glance moved on. It was it seemed, too hot for hagiography.

Wilde’s grave became such a focus of martyrology that the limestone was damaged by hundreds of lipsticked kisses marking genuflection. Cleaning wasn’t entirely successful and made it more porous, risking a cycle of degradation. Hence a glass wall was erected, which worshippers can kiss to their hearts’ content, and which are regularly cleaned off.

There are good reasons. Unlike those in the abandoned telephone boxes, the resident has living relatives who are upset at the desecration. The memorial itself is a fine sculpture by Jacob Epstein (he has a much more modest plot in Putney Vale) which deserves preservation, though someone found the exaggerated testicles offensive enough to hack them off so they had to be replaced.

And yet, despite my admiration for both writer and sculptor, I think there’s an argument for not protecting it. Ostracized, exiled, Wilde was sure that even his name would cause shudders for years. Those thousands of kisses mark not just a rehabilitation but a positive welcoming that shows how mores change over time, while the damage that they do reminds us that love can be as corrosive as it can be positive.